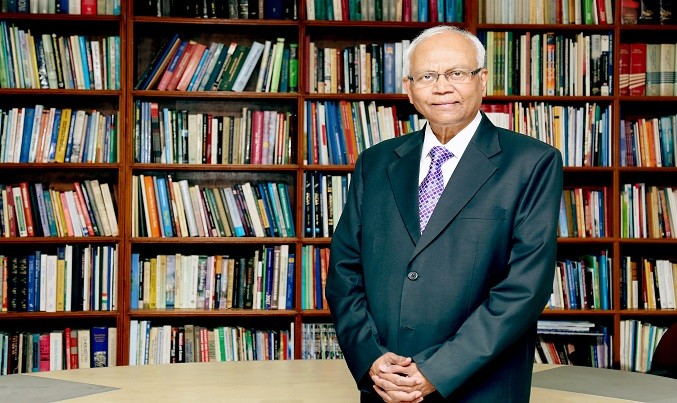

When Raghunath Mashelkar’s daughter Shruti sought to organize the belongings of her deceased grandmother, Anjani Mashelkar, she did not expect to find what she did. Tucked under her grandmother’s saris was some money, and a handwritten note.

This was money that her son, Mashelkar, had given her over the years, whenever he boarded the flight from his hometown Pune to his workplace Delhi, where he was then working as the director-general of Centre for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) India.

The note simply said, “Ramesh, you are a scientist. Use this money to do some good science for the good of the poor people.” This was, as he says, “a simple but a very powerful message” and went on to become the inspiration behind the eponymous Anjani Mashelkar Inclusive Innovation Award.

Now in its tenth year, the award has helped ideators from different fields help bring their products to the market. From low-cost breast exams to a Day 1 dengue test, from environment friendly adult diapers to a machine that replaces manual scavenging, the ideas are marked not only by their innovation but by the social problem they solve, keeping in mind the purpose of the award: to do good for the people.

“The challenge was how do you create goods and services that are affordable to the poor,” says 77-yearold Mashelkar, a Padma Vibhushan awardee. “And at the same time, we must recognise that the poor have aspirations for quality, for excellence. That means we had to bring together two contradictory terms. One was affordability and second was excellence.”

In fact, his work is often quoted in the context of India successfully defending the opposition to the U.S. patenting basmati rice, and the wound-healing properties of turmeric. He pioneered Gandhian engineering, a concept that emphasizes doing more for less, for the good of the many. His work has been marked by a concern for the poor and a focus on indigenous innovation.

Therefore, it comes as no surprise that his 2018 book, “From Leapfrogging to Pole-vaulting: Creating the Magic of Radical yet Sustainable Transformation,” co-authored with Ravi Pandit, sets to lay out the principles that will help companies achieve just that. The book recently won the Best Business Book of the Year 2019 at the Tata Literary Festival, Mumbai.

ASSURED innovation, a framework that is also used to evaluate entries for the Anjani Mashelkar award, focuses on the principles of A (Affordable) S (Scalable) S (Sustainable) U (Universal) R (Rapid) E (Excellent) D (Distinctive) innovations to evaluate not just the inclusivity of an idea or product but also its success.

The ASSURED model has now been adopted widely in various forums: the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation uses it for selection of technology. It is spreading to other ministries like the Ministry of Skills & Enterprises, and the Ministry of Textiles. Bombay Management Association (BMA) has set up an annual award “BMA ASSURED Enterprise Awards”, and national awards, such as Earthcare Awards, Marico Innovation Foundation Awards, and ICC-FICCI awards have used this framework as a first screen for the jury. There is even a proposal to use it in government for purchase processes and public procurement.

Mashelkar represents that brand of scientist who is determined to use science for public good. iMPACT sits down with him to understand how social transformation can occur within the context of corporations and civil society organizations, its intersection with public policy, and much more.

iMPACT: You have spoken a lot in the book about ASSURED, and how they combine to create the perfect recipe for sustainable social change. You’ve also shown how companies and products can change their ASSURED status over time. If it comes to choosing one factor over the other, do you think any one factor of ASSURED is most critical? If so, which?

Ramesh Mashelkar: Each of the elements—namely affordability, scalability, sustainability, universality, rapidity, excellence, distinctiveness— is important. They are all interrelated, though. But I suppose “sustainability” is the most crucial as it is allencompassing too. Sustainability depends on several factors. First is economic. One must have a robust business model. One can’t depend on government subsidies, for instance. Second, is environmental. If it is not green, it will not be good for either industry or society. Third, society must accept it. Genetically Modified Organisms (GMO), nuclear energy, onshore wind, etc. are not acceptable to many societies. Fourth is policy, regulations, etc. A sudden change, say, in emission norms, can affect sustainability if there is not enough time to adjust. Further, in a VUCA world, i.e. in a world that is described by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity, resilience is important. But if you think of it, all the other elements of ASSURED fold into sustainability, if it is interpreted in broad terms.

Today, there are hundreds of solutions that are trying to solve education and health crises. For instance, there are 4574 ed-tech products in India today, and around 17,000 products globally, many of them solving the same problem, leading to resources being distributed and not concentrated. How can that fragmentation of resources be solved, and do you think that is even necessary? This is especially keeping in mind the urgency of some of the problems, especially related to Energy and Environment.

That is where, from the ASSURED framework, the D (i.e. the Distinctive) part becomes most crucial. In the 4574 ed-tech start-ups that you mention, many of them will fall out, because they will be too many “me-too”s there.

Distinctiveness is judged at different levels. Are the aspirations for local or global markets? If global, does one have IPR (Intellectual Property Rights)? If one does have IPR, then how strong it is vis-a-vis the competitor? Are we sure that as one grows, one’s IPR is so strong that it can withstand a potential infringement suit?

In short, I will say that let all these ed-tech start-ups be evaluated in the ASSURED framework. The answers will fall in 3 categories. Not viable, viable for a short time, and viable with long-term sustainability.

You mention the role that an “engaging ecosystem” plays in the success of transformational businesses. This includes public policy and in a country like India, influencing public policy seems like a tall ask from an entrepreneur. It’s also the trickiest of the levers. How can this be best effected, in your opinion?

What you say is absolutely right. It is difficult for any individual entrepreneur to influence a change in the government policy. But when it comes to policy, there are two distinctly different aspects.

The first is for the enterprise to align with the current policy and not go beyond the limits of the existing policy regime to ensure stability.

The second is being able to anticipate the policy changes that are likely to take place in the near or the distant future. As we see around the world, policy changes take place continuously in line with the changing socioeconomic and political environment, both nationally and globally. What is important is to keep a continuous eye on trends and risk analysis based on detailed analytical studies.

As regards influencing government policy, a single entrepreneur cannot do much about it, but there are different forums which can be used to push for changes. They could be industry associations such as CII (Confederation of Indian Industry), FICCI (Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry), ASSOCHAM (Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India), etc. They could be think-tanks such as Pune international Centre, which keeps on bringing out important policy papers, which are prepared by full consultations with diversity of stakeholders.

Also, the government creates many forums for giving voice to entrepreneurs. Let me give you a personal example. In Maharashtra, we have the Maharashtra State Innovation Society. I am the co-chairman of this body with the minister of skill development and entrepreneurship being the other co-chairman. A couple of years ago, we brought out the Maharashtra State Start-Up Policy. But before we set up the policy, we consulted all the start-ups to understand what were their pain points. The policy was designed to take care of the pain points. For instance, one of the pain points was that for every start-up it was difficult to win a tender, which required minimum years of experience for the start-up. So we created a special work order process for the start-ups. To create a further driver, for public sector enterprises, we made it mandatory that at least 10% of their procurement should be from the start-ups. We started giving work orders to these fresh start-ups for assigned tasks with government bodies and this has created enormous benefit by giving the start-up a speedy start.

With your experience with the Anjani Mashelkar awardees, what do you think social entrepreneurs need right now? What are their personal and systemic bottlenecks preventing them from reaching their vision as presented in their PPTs?

I would highlight 4 things. First is capital. Our normal venture capital will not work, since it tends to sometimes be “vulture” capital, with a focus on short term profitability. They require patient capital, sometimes not loans but grants, may be from trusts and foundations or even from CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) funds. I have myself helped some start-ups get funds through such instruments. Second, they do require mentorship, as the journey from idea to impact requires guidance on both speed and direction but also patience and perseverance. Third, support from conducive public procurement policy, such as what the Maharashtra Government has done, will help them with a good and confident start. Fourth, now that tools like ASSURED are available, they can use them for continuous self-assessment to ensure that they will not fall short in any of the critical elements at any time in their journey and they will have assured success.

What role do awards and recognition such as the Anjani Mashelkar award play for emerging social entrepreneurs?

Over and above recognizing fantastic Indian innovations, the award presents an opportunity to spur and fuel innovation for the benefit of the most disadvantaged sections of society resulting eventually in their inclusion into the mainstream. It also has another equally important aim: to sensitize other innovators about the problems faced by some sections of society and to urge them to use their talents to solve problems that “need to be solved” and not those that “can be solved”.

Though the monetary reward is a humble Rs. 1 lakh, the Anjani Mashelkar Foundation and its trustees go over and above to help winners—from mentoring young start-ups to connecting them with the who’s who of the business and policy world. I personally take them under my wing and spread the word about them and their impressive achievements wherever I travel across the world. Audiences are astounded globally when I share such Indian innovation stories with them—not just because of the innovation, but also because of the empathy and grit displayed by innovators in equal measure.

How do you see the future of social transformation vis-à-vis NGOs and social entrepreneurs? Do you think that NGO activities must eventually give way to social entrepreneurship, keeping in mind free-market economics?

I don’t think it is “this or that”. It will be “this and that”. In other words, NGOs and social enterprises will co-exist, as both have a distinct role.

Social entrepreneurship combines a market orientation with a social purpose, generating both financial and social revenues. To me, this is “doing well by doing good.”

NGOs, on the other hand, are focused on doing good, but they depend on external grant funding. Facing the reality of dwindling grant funding, many NGOs are looking at enhancing their sustainability, diversifying their income success, and becoming less dependent on external funding, with all the vulnerabilities associated with it in this VUCA world.

I do feel that social enterprises will deliver social good with greater speed, scale, and sustainability. However, at the same time, we require NGOs who can act as neutral umpires with open minds, who are not radical activists, who promote “development without destruction” and who work with great purpose, perseverance, and passion.

Working in S.T.E.P.: The Katraj Zero-Garbage Ward Model, Pune, India

“In our book, we have shown the prowess of interdependence of four key levers—Social engagement, technology, economic model, and public policy. We call them STEP. This is what is required for transformational ideas to get transformed into real impact on the ground,” says Ramesh Mashelkar.

The model worked to make a ward (division of a municipality or corporation) nearly zero-garbage. But how did it work?

Social engagement:

The populace was initially indifferent to waste segregation. Over 1900 individual volunteers, 10,000 corporate volunteers and the Janwani, a not-for-profit organisation in Pune collaborated to conduct over 1200 social engagement and awareness initiatives, from distributing bins for waste segregation to door-todoor awareness campaigns to street plays and rallies.

Public policy:

The project was run in partnership with Pune Municipal Corporation (PMC). Successive mayors of the city supported the drive, and key comparators actively participated in its vision and implementation. The city administration took practical steps to get the project going, Janwani helped PMC prepare by-laws for sanitation and waste management, resulting in laws mandating waste segregation at source, and composting facilities.

Technology:

A bird’s-eye view of the model might make the role of technology almost invisible. However, through GPS systems to optimize collection routes, mobile apps to monitor “chronic spots”, and grievance redressal apps, technology was at the root of the model’s functioning.

Economics:

The model made perfect economic sense with a payback period of three to five years. The model required citizens to pay a user fee. In case of shortfalls, a tipping fee was calculated based on output of waste disposal, instead of waste collected.